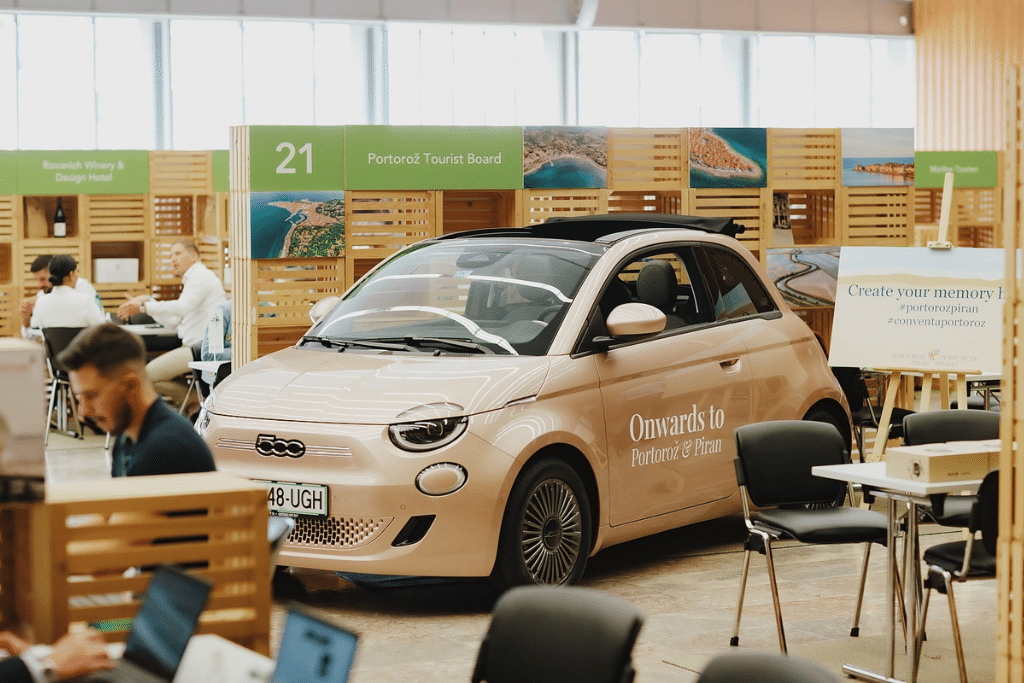

IS DRIVING AN ELECTRIC VEHICLE TO AN EVENT ACTUALLY ENVIRONMENT-FRIENDLY?

The editorial board of Kongres Magazine has been closely following and analysing various sustainability marketing campaigns. It seems their numbers have skyrocketed this year. As it turns out, many of them are misleading and purposefully used by greenwashers to increase sales or improve a company’s reputation. By doing so, they deceive well-intentional consumers and, ultimately, do not contribute to solving ecological and social issues. It is vital to stay aware of the ways in which they attempt to outwit us. Recognising greenwashing is how we can reduce its influence on our choices.

We have decided to prepare a series of articles that will uncover such practices and, hopefully, contribute to a more responsible meetings industry.

Case 13: USING FAVOURABLE GREEN TERMS

Type of greenwashing: Ambiguity and vagueness of claims (using broad, poorly defined terms that can be misinterpreted easily)

Recently, we received an invitation in our inbox to attend a renowned event by going with the most prestigious, sustainable, green and luxurious electric limousine with zero emissions. The sheer number of claims in one sentence made us read it twice. For that reason, we conducted a brief survey on LinkedIn to find out what our community thinks of it. The answers showed the following:

Do you believe driving to an event with an electric vehicle is:

– Green 23%

– Sustainable 33%

– Carbon-free 10%

– Carbon-neutral 35%

The results show all answers received similar votes, apart from the carbon-free answer. That means the respondents were not univocal. Our survey shows how we can be easily misguided by superlatives.

Facts: Experts say we must consider the entire lifespan of a vehicle to solve this dilemma. The lifespan spans from vehicle production to dismantling and must be assessed according to the LCA analysis. Gašper Gantar, a Slovenian expert in the field, approached the calculation by taking the moderately-priced VW Golf as the case study of a vehicle type and presupposed the vehicle completed 300,000 kilometres in its lifespan. The results showed that a petrol-charged car did worst, emitting 52 tonnes of emissions in its lifetime. A diesel-powered car did not fare much better. The emissions by an electric vehicle are comparably lower – 32 tonnes of CO2.

Compared to producing vehicles with internal-combustion engines, the making of electrically-powered vehicles has proven to be more detrimental to the environment. The carbon footprint of producing just one amounts to nearly 7 tonnes of CO2-e, while the carbon footprint of producing a diesel or petrol-powered vehicle is 4,5 tonnes of CO2-e.

We recommend checking how sustainable your vehicle is at https://www.greenncap.com/. They use stars to calculate a car’ sustainability, similar to a safety test. You can check how green your vehicle is on their website.

The moral of the story

The future of mobility is undoubtedly electric, be that good news or bad. Using electric vehicles is also friendlier to the environment, yet not carbon-neutral or carbon-free. For starters, electric vehicles should be fueled by energy from renewable sources (In Slovenia, the percentage of energy acquired from renewable energy sources is below 25%). Thus, we have a long path before reaching carbon neutrality. Our recommendation for event organisers is to write that you will use environment-friendlier vehicles to transport attendees. Such a claim guarantees transparency and helps you avoid any form of greenwashing.

Note: We look forward to hearing about your perspective on electric vehicles and their supposed environment friendliness.

Environmentalist Jay Westerveld coined the term “greenwashing” in 1986. While on an expedition to Samoa, he was greatly upset by the hotel sign concerning the reuse of towels. He concluded that its purpose was solely a strategy to lower expenses instead of the hotel’s sustainable and responsible aspirations.

Westerveld was the first to use the term greenwashing in his expert article, and the rest is history. The term has survived till today and encompasses all areas of sustainability, including gender equality, poverty, hunger, health, education, paid work etc.

There are several typical examples of greenwashing. They have been around for some time, yet, we continue to be duped by them. We have summarised the most typical examples of greenwashing below:

1. Presenting information selectively

An example of greenwashing is emphasising environment-friendly information whilst withholding negative information. A typical example is ignoring the carbon footprint of event transfers which can amount to 75% of an event’s entire carbon footprint.

2. Lack of proof to back up claims

Let us suppose a company claims their event is green or eco-friendly but does not enclose any concrete proof. They should at least calculate their event’s carbon footprint and support it with a certificate issued by an official institution.

3. Ambiguity and vagueness of claims

Another way of misleading is using loose and undefined terms that are nearly impossible to understand in one way. A recurring example, for instance, is stating that an event is carbon-neutral without elaborating what that stands for.

4. Deceiving and irrelevant labels

Companies will often refer to certificates and labels that, in fact, do not exist or are misleading. Lately, there have been cases of green venue finders with no real foundation. This type of deception is embodied by companies that sell “products without CFC”, even though chlorofluorocarbons are forbidden by law.

5. Highlighting the lesser evil

Event organising is environmentally unfriendly. Hence, the claim that one event is greener than another is plainly false.

6. Selling lies

On occasions, companies choose to proclaim lies. Making false claims, certificates, and inventing facts will mislead customers.

7. Meaningless labels

Certificates, labels and awards can often have little or no meaning. In some cases, organisations even award themselves with certificates or endorsements not backed by any authority.

There are even cases when companies tell outright lies. Sooner or later, such practices are exposed, and information about them spreads like wildfire.

In Britain, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) is reporting a boom in the number of complaints about environmental claims – up from 117 in 2006 to 561 last year. “What we are seeing is claims about being carbon-neutral, zero-carbon emissions and use of words such as sustainable and organic,” says Lord Smith, chairman of the ASA.

About the author

Gorazd Čad is a seasoned meeting planner who has dedicated 25 years of his life to the meetings and events industry. He witnessed the fall of Yugoslavia, the establishment of independent Slovenia, adapted to the internet revolution of the ’90s, overcame the economic crisis of 2008, the 2010 eruption of an Icelandic volcano, and the 2019 meetings industry burnout, 2020’s corona crisis and more. Among other things, Gorazd Čad is a professor of geography and history who is sincerely worried about the planet’s future. He strives for events that will be environmentally friendly and responsible to attendees and society.

Slovenian Advertising Code on greenwashing

What the Slovenian Advertising Code says about greenwashing:

Article 17: ENVIRONMENTAL ARGUMENTATION

17.1

Advertising that includes environmental argumentation should be presented in a manner that does not exploit the consumer’s environmental concern or his potential lack of knowledge about environmental themes. It should not contain claims or visual representations that could, in any way, mislead the consumers about products’ benefits from an environmental viewpoint or the environmental activities the advertiser will conduct. Messages can apply to concrete products or activities; they cannot, however, unjustifiably imply that they cover all activities of a company, group or sector.

17.2

Claims concerning environmental preservation are not allowed to be used groundlessly. Claims such as environment-friendly, completely biodegradable, greener, friendlier or organic may be acceptable, provided the advertisers prove their truthfulness.

17.3

Comparisons are acceptable if the advertisers can prove that their product improves from an environmental perspective compared to their own or competitors’ products.

17.4

Claims and comparisons can be misleading if they leave out important information.

17.5

When scientific opinions are divided, and the results are not final, the advertisement has to make that clear. An advertiser cannot quote that their claim is generally accepted if that is not the case.

17.6

In case a product never had any evidently harmful effects on the environment, the advertisement cannot suggest that its structure was altered to make it more environment-friendly. It is, however, lawful to quote claims about a product whose composition has been altered or has been used hitherto without ingredients that are known to be harmful to the environment.

17.7

The use of lesser-known expert terms should be avoided. If the use of a scientific term is unavoidable, its meaning should be clear and understandable or additionally explained.

17.8

A broader explanation of the most commonly used claims and terms is defined in the International Chamber of Commerce Code of Advertising and Marketing Practices.

For more information please check: https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2018/09/icc-advertising-and-marketing-communications-code-int.pdf.